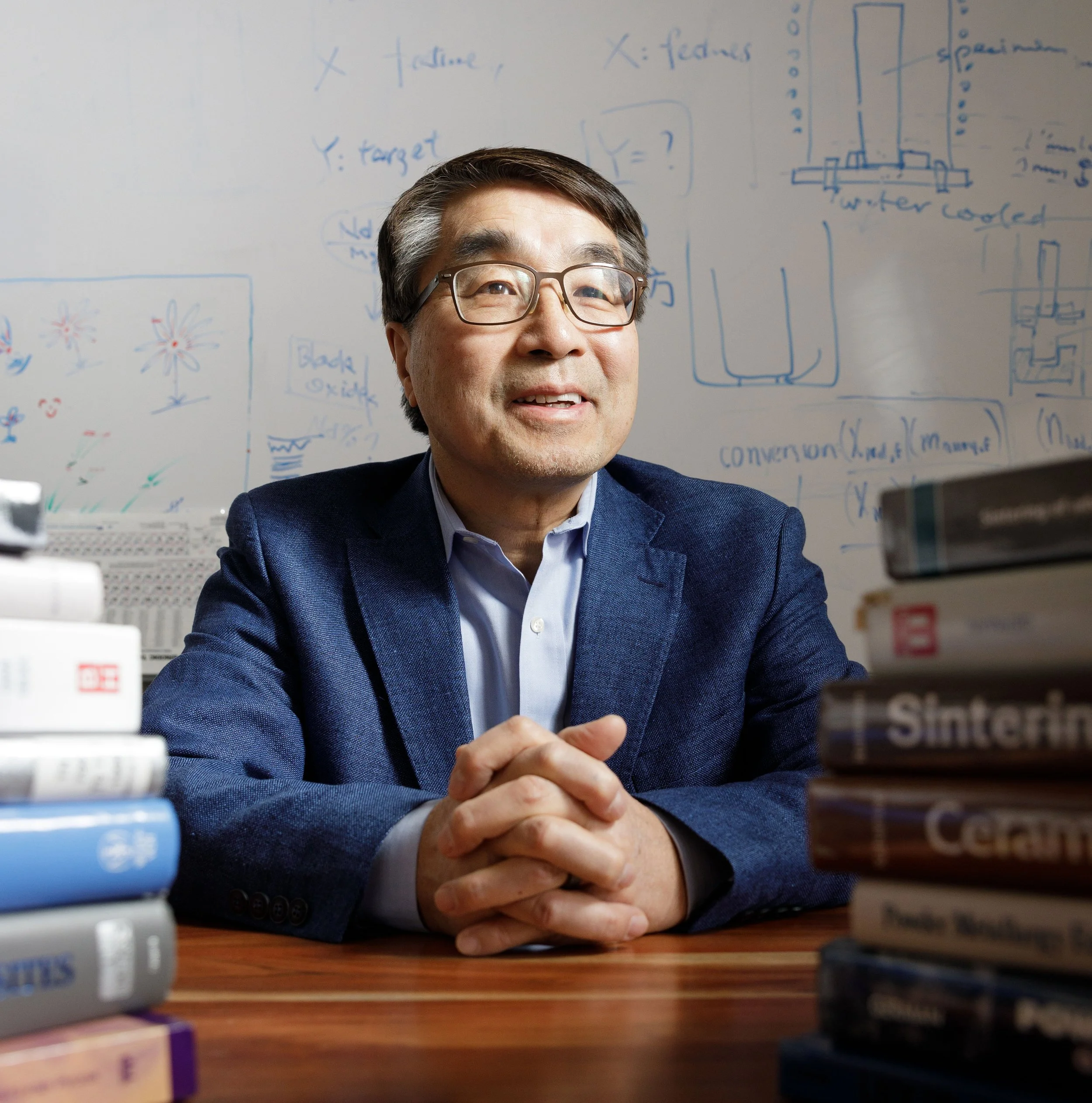

DR. ZHIGANG FANG

Scientific Innovation

By Golda Hukic-Markosian, PhD. | Photography by John Taylor

Titanium should have taken over the world by now. It’s light, strong, corrosion-resistant, and so biocompatible that surgeons trust it more than any other metal. By all logic, titanium should be everywhere: in our cars, appliances, electronics, even the tools we handle every day. So why isn’t it?

That question brought us to Dr. Zhigang “Zak” Fang, a soft-spoken and remarkably humble professor at the University of Utah whose groundbreaking research may finally remove the barriers that have held titanium back for more than 70 years.

A Scientist Shaped by a Time Without Science

Dr. Fang grew up in China during the Cultural Revolution, a period in which universities were effectively shut down and access to higher education was extremely limited.

“As young people at that time, if we had a chance to go to college, we grabbed it,” he recalls. “It didn’t matter what it was.”

He was assigned to study metallurgy at what was then called the University of Iron and Steel Technology in Beijing. “I did not choose this,” he says. “But I guess I had some natural inclination to do technology.”

Like many Chinese students of his generation, Dr. Fang hoped to pursue advanced study abroad. He came to the United States in 1987 and completed his graduate studies in Alabama. After earning his PhD, he spent nearly eleven years in industry — first in Arkansas, then in Houston — specializing in tungsten carbide for oil and gas drilling.

“You think about it,” he says. “You have to drill a hole 5,000, 10,000, 20,000 feet deep to get to the gas and oil. So the material for that drill bit is extremely important.”

Those years under intense industrial demands shaped how he understood metals under stress; a perspective that would later influence his approach to titanium.

In 2002, a faculty position opened at the University of Utah. Dr. Fang accepted, moved to Salt Lake City, and eventually shifted his research toward a metal he now studies more deeply than most metallurgists: titanium.

Why Titanium Is Extraordinary and Infuriating

Titanium occupies unusual territory in the periodic table of modern life. Lightweight yet strong, resistant to corrosion, and gentle to the human body, it appears everywhere from knee replacements to jet engines.

But titanium also hides a stubborn secret: it loves oxygen a little too much.

“Titanium is very abundant in the earth,” Dr.Dr. Fang explains. “But it has a very strong affinity for oxygen. In minerals, it comes as titanium dioxide, and breaking that bond takes a lot more energy than breaking iron oxide.”

This leads to two major problems:

1. Extracting titanium metal is extremely difficult.

The conventional method called the Kroll process converts titanium oxide into titanium chloride using chlorine gas, then reduces it with magnesium at high temperatures. The steps require large furnaces, corrosive chemicals, and energy-heavy distillation. This process dates back to the 1940s but remains the global standard.

2. Even after becoming “metal,” titanium still dissolves oxygen.

This is the part most people never hear about.

“Titanium can dissolve oxygen the way water dissolves sugar,” Dr. Fang says. “Once it holds too much oxygen, its properties aren’t good anymore. It becomes brittle.”

Removing that oxygen — refining the metal to low-oxygen, high-performance form — is extraordinarily expensive.

“This is why anything made from titanium is twenty times more expensive than steel,” he says. “Not because titanium is rare, but because it is difficult to process.”

For decades, governments and companies have tried to replace the Kroll process. According to Dr. Fang, “there must be twenty or thirty ideas” proposed over the years. Some received major funding. None transformed the industry.

The problem remained: titanium’s bond with oxygen was simply too strong, until Dr. Dr. Fang’s group found a way to weaken it.

The Breakthrough: Using Hydrogen to Break an Impossible Bond

Dr. Fang’s innovation, the HAMR process, short for Hydrogen Assisted Metallothermic Reduction, did not appear all at once. It emerged from years of analyzing the real bottleneck in titanium production: not the initial reduction of oxide to metal, but the removal of dissolved oxygen afterward.

“Our approach was problem-driven,” he says. “We looked closely at where the energy consumption is, where the real challenge is. We realized the key issue is refining titanium that contains too much oxygen.”

Then came the insight that changed everything:

Hydrogen destabilizes the titanium–oxygen bond.

“When hydrogen dissolves into titanium that contains oxygen, it weakens that bond,” Dr. Fang explains. “That makes the oxygen removal a lot easier.”

In the HAMR process, titanium oxide or oxygen-rich scrap is exposed to hydrogen and reacted in molten salt with magnesium. Magnesium has an even stronger attraction to oxygen than titanium does. It strips oxygen away, forming magnesium oxide as a byproduct, and leaves behind titanium hydride — a low-oxygen precursor that can be converted into pure titanium powder.

The impact is profound:

Much lower energy use than the Kroll process.

No chlorine, no high-temperature distillation.Reclaims scrap titanium that normally oxidizes and becomes unusable.

Cuts production costs by 30–80%, depending on the product stage.

For the first time in decades, titanium finally has a viable alternative to the Kroll process.

From Utah Research to National Industry

The University of Utah licensed Dr. Fang’s technology to IperionX, which is now building a major titanium production facility in Virginia. Their first phase will focus on recycling titanium scrap, a faster, more economical starting point before moving to full production from ore.

“They’re well underway,” Dr. Fang says. “They already built a very large facility. They have potential customers waiting for their process to scale up.”

The timing is significant. In 2020, the United States closed its last facility for producing primary titanium metal. The country still manufactures titanium components but the metal itself is 100% imported, much of it historically from Russia.

“For defense and aerospace, we can’t rely completely on other countries,” Dr. Fang says. “IperionX wants to reshore titanium manufacturing, not by political means, but with better technology.”

The Department of Defense agrees. According to the company’s publicly available report they already secured substantial federal funding because lighter military vehicles, improved armor, and domestically sourced titanium have obvious national security implications.

Their target is ambitious: production of 1,000 tons of titanium per year by 2027, and dramatic expansion by 2030.

If they succeed, titanium may finally move beyond aircraft and medical implants into the broader world of stainless steel, a market Dr. Fang calls “huge.”

The Human Side of a Materials Revolution

Despite the scale of his work, Dr. Fang speaks most passionately when discussing his students.

His group includes 17 to 18 researchers: PhD candidates, postdoctoral scholars, a research professor who was once his student, and undergraduates who often begin with simple tasks and evolve into confident young scientists.

“At first they seem like helpers,” he says. “But over time our goal is to make them independent researchers.”

He meets with each one weekly. They discuss data, problems, and next steps. But he also teaches something less tangible: how to think.

“They acquire a way of looking at engineering problems,” he explains. “A mental process — how you identify the real challenge and ask the right question.”

He smiles when describing how undergraduates discover joy in research after working retail, restaurants, or manual labor jobs. “To work in a lab is much more interesting to them,” he says.

For a man reshaping global titanium production, he speaks about his own legacy in startlingly simple terms: students learn how to think and how technology can improve life.

Dr. Fang has received major recognition for his titanium work, including the Humboldt Research Award and the global R&D 100 Award. But he doesn’t linger on accolades. He returns, again and again, to the question that started it all: Why does titanium cost so much, and what if it didn’t?